New novel by UW–Madison French professor explores love and loss in the early years of the AIDS crisis

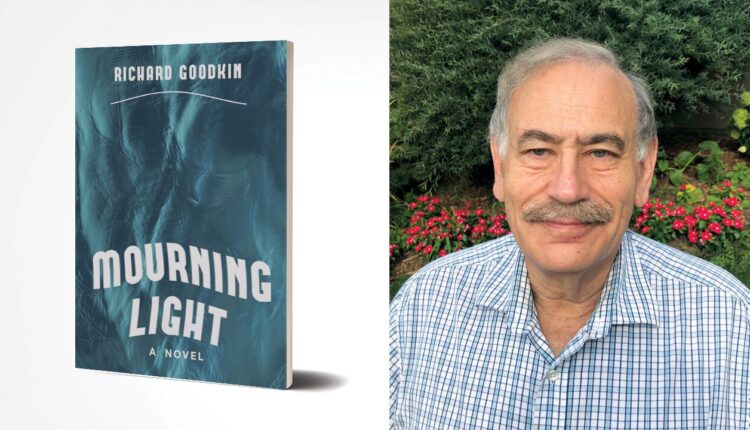

Richard Goodkin wrote the first draft of what would become his new novel, “Mourning Light,” over the course of a few months back in 1993. For the University of Wisconsin–Madison French professor, working on the novel was a way of processing some difficult personal emotions surrounding the loss of his partner two years earlier — and so he wrote a fictionalized story about a UW–Madison professor who loses his partner during the early years of the AIDS epidemic. Now, three decades and countless drafts later, the semi-autobiographical love story will be published by the University of Wisconsin Press and celebrated with a launch event at Room of One’s Own bookstore on July 18.

“The process of writing the novel was a rollercoaster. … There were years where the manuscript lay fallow,” says Goodkin, who has also published a historical novel written in French and five monographs on 17th, 19th and 20th-century French literature — nothing so personal as “Mourning Light” (originally titled “ Who Killed Anthony?”), half of which is set in Madison and rich with details that locals will recognize and appreciate. And although Goodkin’s exploration of grief through the novel’s premise feels highly personal, that’s where the parallels stop in this lovely, slim novel that is anchored by a psychological, grief-driven, love-triangle mystery influenced by Daphne du Maurier’s seminal book, “Rebecca .”

“The story is thoroughly fictionalized — the truth is that my late partner and I do not particularly resemble the main characters in personality, and the story itself is completely fictional,” he says. “The most meaningful resemblance to my own experience is the view of mourning that comes out of the novel, and that is something that I believe it is worthwhile to share with others who may be struggling with some of the things I struggled with as well. ”

When you returned to your novel draft three years ago to begin the publishing journey with UW Press, had your relationship with grief changed from that nearly 30-year-old draft?

I actually don’t think my relationship with grief had changed, but my relationship to the story had changed. The passage of time allowed me to take more distance from the story in a good way — the narrative voice changed and became much more distinct from my own voice, and I felt freer with the material. I would say the central thrust of the novel never really changed, but the story became more focused and more unified. The idea of incorporating du Maurier’s “Rebecca” into the story was one among several key elements that were added long after the initial draft. I started out writing with only a few rudimentary ideas about where the story might go — the truth is I had almost no idea of how it would end until I was nearly finished with the first draft. After that initial period of a few months in 1993 when I wrote the first draft, the process of rewriting has had its ups and downs: it’s been an amazing learning experience, but it’s also difficult not to get discouraged when something one finds very important and meaningful takes so long to come to fruition. About three years ago I decided to revisit it, and that’s when I came up with the basics of the version that’s been published (after some further revisions in response to excellent suggestions from UW Press and the external readers of the manuscript).

Was there anything significant about the plot or themes or characters that changed?

One thing I reworked and deemphasized was the question of how Anthony became infected with HIV. In the earlier drafts that was a key question — hence, among other reasons, the original title, “Who Killed Anthony?” But ultimately I decided that that question was drawing attention away from the central theme of the nature of mourning and its relation to the nature of love. Also, the characters of Willis and Molly, Reb’s and Anthony’s best friends, were there from quite early on, but they became more central with each successive draft. As I said earlier, I think perhaps the most important change was that the narrator’s voice changed in subtle but important ways with each successive draft.

What were you ready to explore with this novel that you hadn’t yet in your previous work?

In 1993, when I started it, I’m not sure how much of the excruciating experience of losing my partner I was ready to explore, but I did want to write about the mourning process and how I felt it related to the actual relationship one has with the person who has been lost. I also thought that writing a novel about my relationship with my partner and what it was like to lose him might well be part of the mourning process, since I see mourning as being a process of understanding the loved one and oneself, as well as a process of working through deep and often difficult emotions. Finally, although I received extraordinary nurture and support from family and friends when my partner died, I came to believe — as I still do — that American culture is not particularly conducive to accepting the true nature of mourning; that it is slow, impractical and intimate, and is predicated on not simply moving on quickly to the next stage of one’s life and thus antithetical to our culture, which is obsessed with changing trends and remaining largely free to leave the past behind so as to live fully in the present.

Without giving anything away, one of the clear themes in this book is our relationship with our loved ones after our earthly interactions have ended. Through loss, we process life — theirs and ours. Reb is haunted by his partner’s death, as well as other family members (I found Reb’s childhood backstory so heartbreaking), and he defines himself through these losses. And like his namesake Rebecca, he is haunted by the ghost of someone who was never actually who he thought he was.

Like “Rebecca,” the book is based on a series of misunderstandings that color the main characters’ relationships and also come to influence questions of grief and mourning. I did my best to draw out the idea that subjectivity itself is not completely separable from perspective, that we inevitably view the world through both, and that both affect our ways of mourning our loved ones. In my view this very particularity of each individual — our quirks, idiosyncrasies, flaws and gifts — deeply influence how we make sense of our lives, how we interpret and experience our relationships, and consequently the individual ways we go through the process of mourning.

Was there anything that surprised you or that you were able to process about what life was like for gay and bisexual men during the early days of the AIDS crisis? Did you feel as if you were writing something intimately personal, or did you feel as if you were speaking for a generation?

I was fortunate to come of age at a time when views on sexuality were much more tolerant than they had been in my childhood, for example, although in general I believe there is much more tolerance today than in the 1970s and 1980s, which is when I came of age. In writing the book I don’t believe I ever felt as if I was speaking for a generation — to my mind that sounds presumptuous. Perhaps it would be fair to say that I was aware of telling a very personal story inflected by various forces that were also formative of other members of my generation (and others). And today I am very grateful to live in a time when a story of true love can be told about people whose sexuality would have been a taboo subject not all that long ago, and when, hopefully, people with a wide range of views about and experiences of sexuality are not prevented by the fear of deviating from social norms from identifying with both the joys and the pains of that love story.

It was such a pleasure to read a book set in Madison. I did note a mix of very real and (I believe) fictionalized places in the book. Am I wrong about that? (For example, was the White Rabbit the White Horse Inn?) What sorts of decisions did you make when writing a semi-autobiographical novel set in your current home, and were there any challenges?

You’re spot on about the White Horse Inn! My basic goal in the way I have depicted Madison is to try to give the setting a real sense of the place and of its people without raising questions about the specifics that might be distracting. If someone reading the scene at the White Rabbit fixes on the (alas now defunct) White Horse Inn as a possible model, that’s absolutely fine with me (and it would be just as fine if it weren’t what I myself envisioned for the place ), but the entire city of Madison and its environments plays an important role in the book as a place of tolerance, civility, healing, humor, fun and companionship; a stunningly beautiful city that I loved at first sight in 1988 and am grateful to have lived in for almost half of my life thus far.

Now that such a personal, long-time-coming piece of work is finished and out into the world, do you plan to write another novel?

Good questions. I hope so. My first order of business will probably be shortening the historical novel I published in France in 2013, a story about the great actress Madeleine Bejart, the collaborator and mistress of Moliere, and trying to get it published in English.

Is there anything you’re hoping this book will spark discussion around?

I hope it will encourage people to see mourning as not simply “the time following the loss of a loved one,” but rather a process that involves coming to an understanding of the role(s) that the loved one has played in one’s life and of whether or not there are misunderstandings or unfinished business that are preventing one from going through that process. In my experience, mourning a partner or someone else who is a central part of one’s life is a slow process, and we live in a society that discourages dwelling on the past and constantly pushes us to “move on.” Of course there is something good in that perspective as well, but mourning takes the time that it takes, and I hope that my story gives an example of why it is worth taking that time.

A launch event for “Mourning Light” will be held at Room of One’s Own bookstore on Monday, July 18 at 7:00 pm

COPYRIGHT 2022 BY MADISON MAGAZINE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THIS MATERIAL MAY NOT BE PUBLISHED, BROADCAST, REWRITTEN OR REDISTRIBUTED.

Comments are closed.